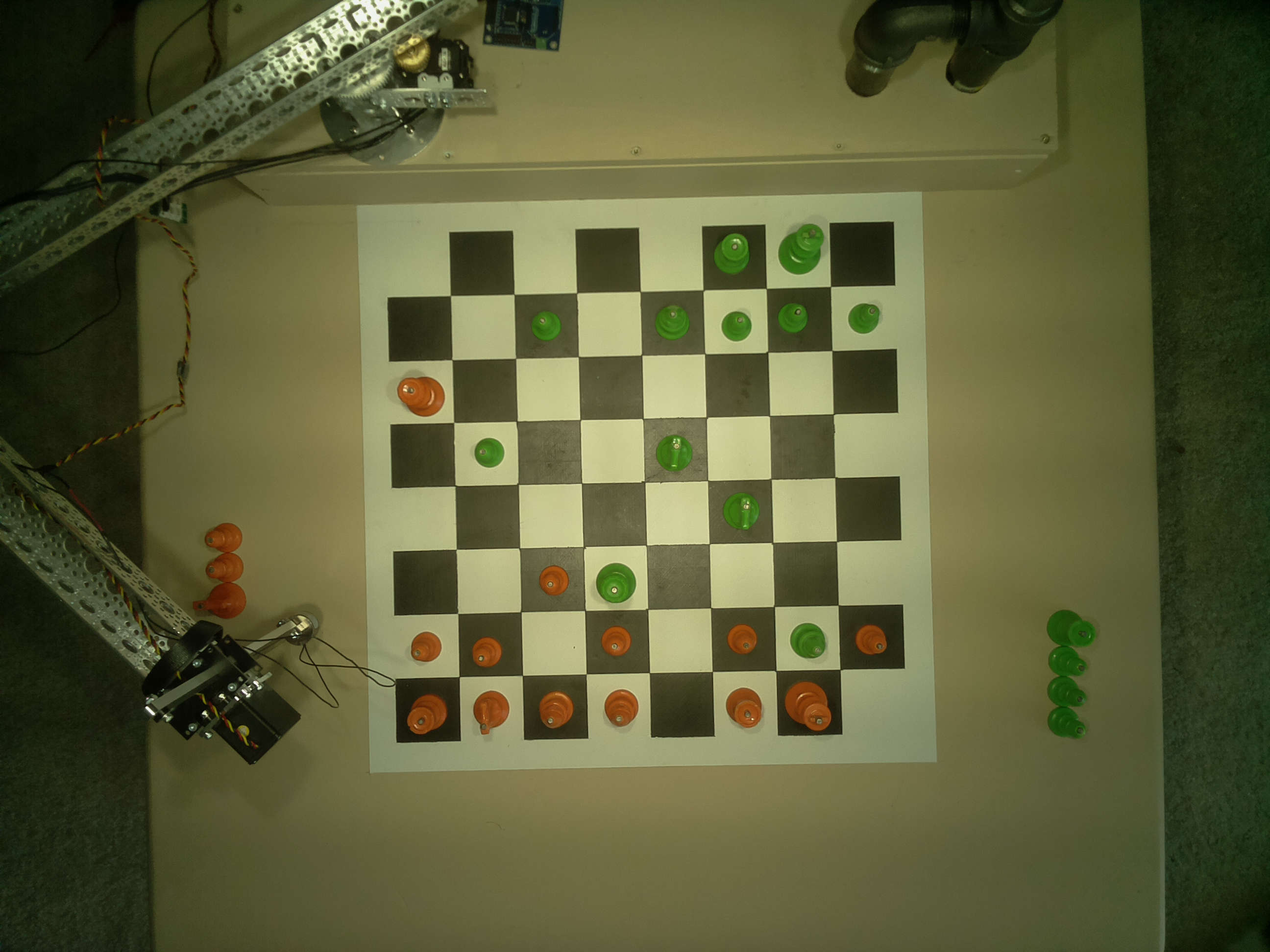

The Raspberry Turk uses computer vision to recognize where the chess pieces are on the board before deciding what move to make.

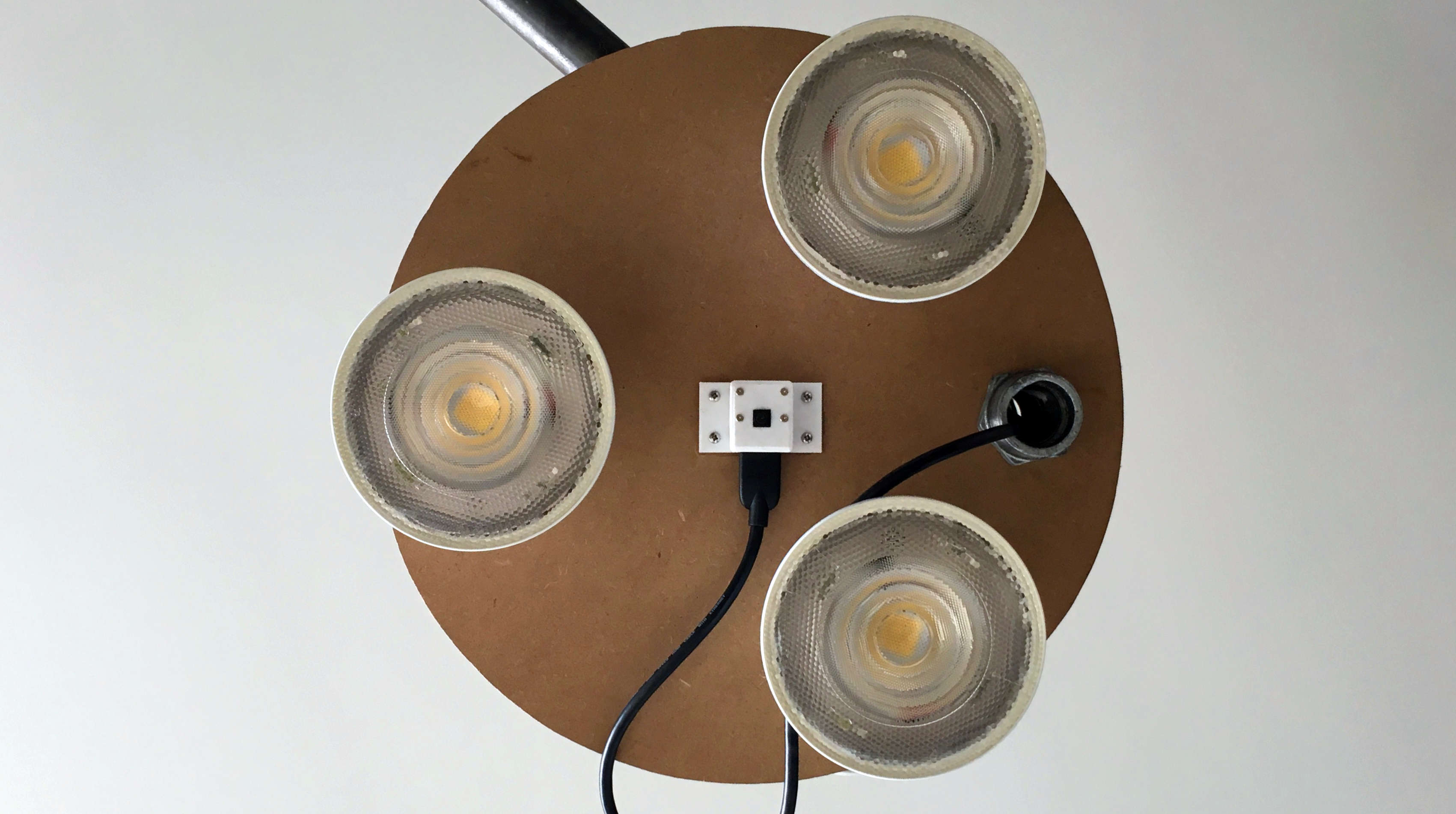

The robot sees through a Raspberry Pi camera module attached with an HDMI cable to a fixture directly above the chessboard. For more information on how the camera is attached, and how the fixture is setup, click here.

The camera is controlled via Python OpenCV running on the Raspberry Pi. The raw image is converted to a 480x480px image by warping the perspective so the chessboard squares are equal size and the non-chessboard part of the image is cropped. A description of the process for finding the correct perspective transform matrix can be found here.

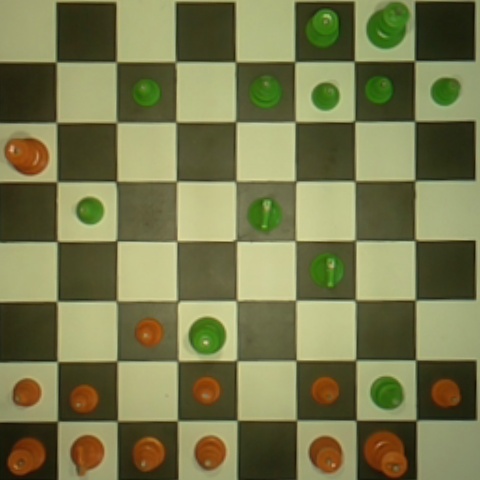

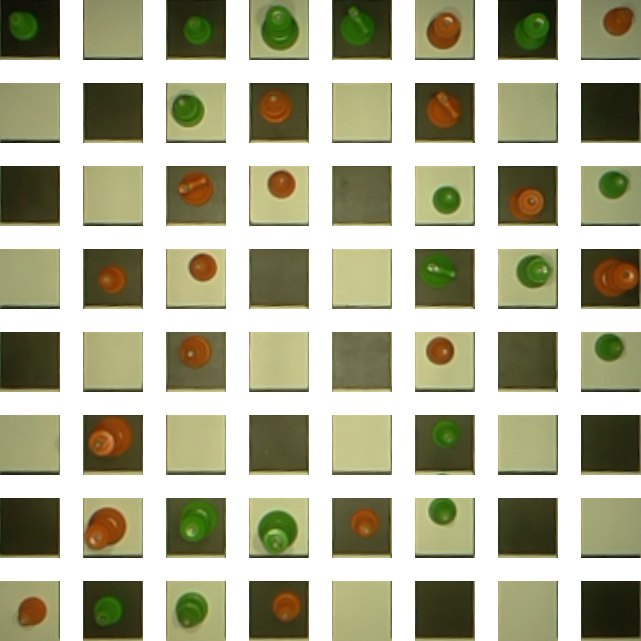

In order to build a system that can recognize which pieces are on which squares of a chessboard by analyzing an image we need a large dataset to train and validate a computer vision model. In order to collect a dataset I wrote several scripts and sat for hours moving pieces to capture multiple placements for every piece in every square on the board. More information on how the dataset was collected can be found here.

Each image is then cut into 64 smaller images and stored with the appropriate label.

This dataset is publicly available on Kaggle, released under the (CC BY-SA 4.0) license.

Instead of trying to figure out what type of piece is on each square, we can take a shortcut. Because we know the state of the game, all we need to do is track which piece moved. By only tracking changes we can internally keep track of which pieces are on which squares.

Our goal is to create an algorithm that can determine whether a square contains no piece, an orange piece, or a green piece. I attempted to solve this problem using both machine learning and conventional computer vision. In the end, I found using support vector machines to be an adequate way of solving the problem. The detailed notebook, with code, used to create this model is here.

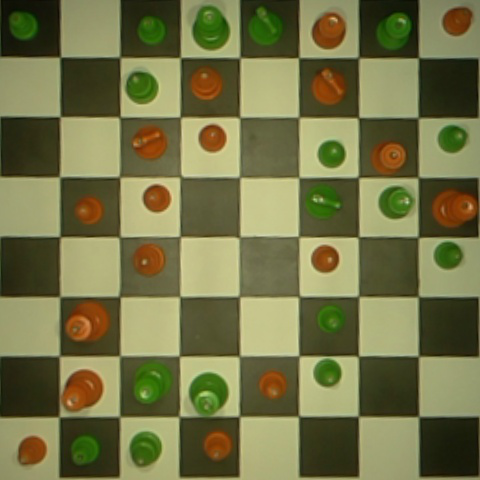

There is a problem with this approach though. What happens in this case?

We could assume that the player will always promote their pawn to a queen, but this is not always what is best. Instead, we can attempt to determine the type of piece using a more complex model. In this notebook, I attempt to use convolutional neural networks and TensorFlow to detemine what type of piece the player promoted their pawn to.